Not so Universal: the two-tiered health element. How the Universal Credit Bill will create a two-tiered system for disabled people.

On this page

The briefing is published in full below. Click here for a pdf 672 KB version of the briefing, and here for an editable Google doc version.

Executive summary

The government's decision to remove cuts to Personal Independence Payment (PIP) from the Universal Credit Bill (UC bill) was the right call. However, damaging and unjustified cuts elsewhere in the health and disability benefits system have been overlooked.

The UC bill will have a devastating impact on disabled people and their families. An estimated 730,000 disabled people will lose out on £3,000 per year, on average. The bill will create a two-tiered system of support, as people who qualify for UC health from the 6th of April 2026 will generally receive a lower rate of support. It won’t help disabled people into work. And people with severe, life-long conditions may miss out on protections.

The government has said that this bill will ‘rebalance’ Universal Credit (UC). They argue that the big gap in income between somebody with, and without, UC health encourages more people to try and prove that they can’t work. This is seen as ‘trapping’ people on benefits. The government claims that by lifting the value of the standard allowance above inflation, and decreasing the value of UC health, people will be incentivised to work. This is wishful thinking.

In reality, this bill will plunge more disabled people into poverty, or deeper poverty. The uplift to the UC standard allowance isn’t large enough to offset cuts for disabled people and isn’t the right way to encourage disabled people into work. And despite assurances to the contrary, as it stands, the bill is likely to leave many seriously disabled people without protection or support.

Several groups of disabled people will be directly affected. This includes those who develop an illness or have an accident after the cut-off date, those whose condition worsens over time, people who lose access to UC temporarily, and disabled children who qualify for UC as adults. There is no clear rationale for why these groups should be entitled to less support.

The UC bill has been designed around savings targets, rather than meaningful reform intended to better support disabled people. The legislative process was rushed and chaotic, with changes brought in without consultation and limited parliamentary scrutiny. As a result, the impact of the bill has not yet been fully debated or understood. This report seeks to help fill this gap.

Introduction

The UC bill cuts the health element of Universal Credit (UC health) by nearly 50%, to £50 a week for new claimants - except those with the most serious, life-long conditions - from April 2026. After that, UC health will be frozen and won’t go up with inflation. For current claimants, and new claimants who meet the new severe conditions criteria, UC health will be maintained at the original rate and uprated depending on the Consumer Price Index (CPI). These changes weren’t consulted on.

The bill also increases the UC standard allowance above inflation until 2029/30. The government predicts this will be a £7 per week increase for 2026/2027, but the exact amount is dependent on CPI in September 2025.

When the bill was originally brought forward on the 18th of June, it also included restrictions to the eligibility criteria for the non-means tested disability benefit PIP. These changes have now been shelved, pending a review of the PIP assessment by Sir Stephen Timms.

It’s welcome that the government listened to the significant concerns raised by disabled people, charities, and MPs about the bill. However, the changes made to UC health are poorly designed and will cause harm to disabled people.

What is UC health?

A UC claim is made up of a number of elements, such as the standard allowance, the housing element, and child elements. Disabled people can currently apply for the ‘limited capability for work and work-related activity’ (LCWRA) element. This is an extra payment, currently worth £423.27 a month.

Eligibility for the LCWRA payment is assessed through the Work Capability Assessment (WCA). This assesses the extent to which the claimant is able to work or prepare for work. The possible outcomes are:

Fit to work - the claimant is found to be well enough to work and will be expected to engage in work search activities and take up any role offered. If they don’t, they’re at risk of being sanctioned.

Limited capability for work (LCW) - the claimant is found to have a limited capability to work and will be expected to engage in work preparation activities, but won’t be required to start work. However, they may work if they choose to do so. If they don’t engage, they may be at risk of being sanctioned. Before April 2017, they also received an extra monthly payment.

LCWRA - the claimant is found to have health difficulties serious enough that they aren’t required to prepare for work or start work. However, they may work if they choose to do so. They receive an extra monthly payment.

In the Pathways to Work green paper, the government set out plans to scrap the WCA in 2029/30 and make the daily living element of PIP the gateway to extra disability payments on UC. They also announced plans to rename the LCWRA payment ‘the UC health element’. In this report, we use the term ‘UC health’ to refer to the current LCWRA payment.

Why is UC health so important?

A UC award helps protect and support people on no or low incomes. Ideally, a person’s time on UC should be short, helping them overcome a temporary break in earnings.

However, for some people, full-time work isn’t a realistic prospect. Some disabled people and those with long-term health conditions may need to receive UC long-term. UC health offers a higher level of financial support in recognition of this.

This was affirmed by the government in the Pathways to Work green paper:

“Financial support from [UC health] will be there to help reduce the risk of poverty, meet extra costs, and take account of lower earnings capacity often associated with long term health conditions and disability.” - point 33, Executive Summary

Without UC health, disabled people who can’t work many hours would be in a financially vulnerable position. They’d struggle to afford their essentials, meet unexpected costs and avoid debt.

Why the UC bill will harm disabled people

Disabled people will suffer

The UC bill cuts the value of UC health from £423.26 to £217.26 a month for most new claimants. It also freezes the payment until 2029, so it won’t increase in line with inflation. This represents a further, real-terms, cut over time.

Cuts to disability benefits matter. Disabled people are already struggling to afford their essentials and avoid debt. In 2024 alone, we helped 110,000 disabled people and people with long-term health conditions access crisis support, including food banks and other charitable support. That’s an average of more than 400 people every working day.

When we polled people receiving disability benefits earlier this year, over 4 in 10 were struggling to afford their essentials, with half having to use savings to cover the cost of these [1]. A quarter were avoiding medical costs, and almost a third were skipping meals to pay their bills [2].

People who qualify for UC health from the 6th of April 2026 will be £3,000 a year worse off, on average, due to the UC bill. Applying the cuts to new claimants will create a two-tiered system of support, based on the date of somebody’s claim rather than their need. Over time, the incomes of disabled people on UC health will diverge further and further.

According to the Bank of England predictions for CPI, by 2028/29 the combined annual value of the standard allowance and UC health will be £10,672 for protected claimants and £8,119 for new claimants.

Figure 1: Predicted annual UC award for people on the original and reduced rates of UC health.

Note: The UC award here includes the standard allowance and UC health. Protected claimants include people who qualify for UC health before the 6th of April 2026 and claimants who meet the new severe conditions criteria. These calculations are the author’s own, using the Bank of England’s CPI forecasts and the uprating calculations given by the UC bill to estimate how the standard allowance and UC health may be uprated over time.

The cuts will leave many disabled people unable to afford their essentials. The people we help with debt who are disabled, out of work and claiming UC already have an average monthly deficit of £26 in their budget after paying for essentials. Cutting UC health by over £200 will push many of the people we help into deeper hardship.

Almost 1 in 3 of the people who came to us for help with UC health in 2024/2025 also needed help with crisis support. More than one quarter needed advice on debt. We expect these numbers to increase as a result of the cuts.

Anita’s story

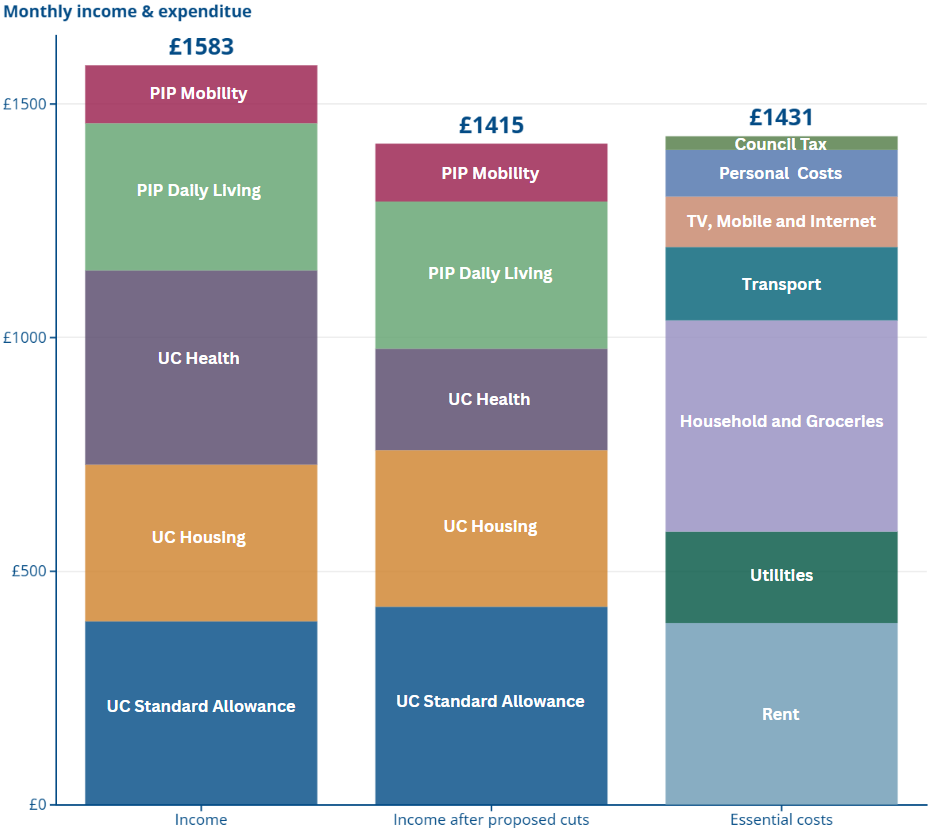

Anita* is a single woman in her 50s. She has severe mental health problems and learning difficulties, but since the pandemic, she has lost all her mental health support. She has regular panic attacks while out in public and struggles to walk due to issues with her feet. She needs help to prepare food and get dressed. She relies on her family to remind her to eat, take medication, change her clothes and manage her toilet needs.

Anita came to us for help with debt. She receives PIP and UC, including UC health. As a result, she currently has £152 left over each month after she has paid her essential costs.

However, if we apply the cut to UC health to her budget, she’d be £16 in the red each month, even with the UC standard allowance uplift. That means she’d be unable to afford her basic essentials and would likely fall further behind on bills. She’d be at risk of eviction, debt enforcement and severe hardship.

* All names have been changed.

Figure 2: Anita’s budget before and after applying the cut to UC health

Note: Anita’s essential costs are accurate for March 2025. Her income before the cuts has been uprated so that it uses the 2025/26 benefit rates. Her income after the proposed cuts uses the 2026/27 rate of standard allowance and reduced rate of UC health to show how the changes would impact her budget if directly applied.

Anita already gets UC health, so she shouldn’t be affected by the cut unless she loses her entitlement. But new claimants won’t get the same protection. Although somebody may have the exact same care needs and costs as Anita, they won’t get the same level of support.

UC health has historically been a key part of boosting the income of disabled people who aren’t able to work. In the Pathways to Work green paper, the government says that UC health will in future no longer be based on a person’s ability to work, but instead help mitigate the lower earning potential and higher costs faced by disabled people. People who become disabled after the cut-off date won’t have lower care costs or higher earnings than those who are currently on UC health, so there’s no reason why they should receive half the support.

The bill won’t rebalance UC

The key rationale for the changes to UC rates is that there is a ‘fundamental imbalance’ between the standard allowance of UC and UC health. The Pathways to Work green paper notes that the UC standard allowance is now worth less than 25% of what somebody working full-time at the National Living Wage could earn and is about half of what people who also get UC health receive. This is described as creating a ‘perverse incentive’ for people on UC to try and claim UC health instead of moving into work. This, in turn, is thought to lead to longer-term unemployment.

It’s assumed that if the gap between the standard allowance of UC, and UC health, were smaller, fewer people would feel the need to apply for UC health, and more would move into work instead.

However, while uprating the standard allowance of UC is a good step, in reality, the uplift is too small to make a meaningful difference. Over the first year, a single person over the age of 25 on UC will gain just £364, while new claimants will lose out on £2,472 because of the cut to UC health.

Figure 3: The annual change in benefit rates for new claimants between 2025/26 and 2026/27.

Note: the rate for the standard allowance is based on the calculations given in the Pathways to Work green paper. However, the exact rate for 2026/27 will be determined by CPI in September 2025.

Whilst these steps do narrow the gap in entitlement, this is overwhelmingly achieved by cutting the health element, rather than raising the standard allowance. This isn’t a ‘rebalancing’ for disabled people.

“Why pretend that [increasing the standard rate of UC] somehow will balance out the loss of money for the people who probably aren't going to get a job?” - Citizens Advice adviser

In addition, the uplift to the standard allowance isn’t even enough to take it back to the level it was in 2014 (in real terms). The standard allowance has been frozen, or increased by less than inflation, year on year, meaning it has lost value over time.

Currently, the standard allowance is worth £400.14 per month for single people over the age of 25. By 2028/29 the uplift will increase this to £459.32 per month. However, if the standard allowance had been increased by inflation every year since 2014, it would be worth £468.07 by 2028/29. Therefore, the standard allowance would need to be increased by a further £8.75 per month for single claimants just to make up for this drop in value over time.

Figure 4: The monthly value of the standard allowance since 2013/14, compared to the standard allowance rate if it had been uprated in line with CPI every year.

Note: the rates from 2026/27 are based on the author’s own calculations, using the CPI predictions given by the Bank of England.

Furthermore, the standard allowance uplift won’t apply to people already receiving the UC health element. The UC bill dictates that existing claimants will receive an annual increase in line with inflation, for their combined standard allowance and health element award. When the former rises by more than inflation, due to the additional uplift, the latter will rise by less than inflation to counteract this [3].

The UC bill won’t help people into work

The government argues that cutting the UC health element will incentivise more disabled people to work. They believe that the current system encourages people to stay out of work, so that they can claim UC health and receive a large boost to their income. In reality, disabled people are allowed to work whilst receiving the UC health element - although our advisers tell us that not everyone’s aware of this.

The UC health element isn’t a barrier to work. It actually makes trying work more affordable, as people receiving UC health have a ‘work allowance’. That means they can earn £411 per month (£684 per month if they don’t receive housing cost support) before their UC payments start to be reduced by the taper rate. Without the work allowance, a person’s UC payments get reduced as soon as they start earning any money.

For example, a disabled person who is paid the National Living Wage and gets housing support on Universal Credit, could work for 4 hours per week without seeing their UC payments reduced. This means that if they work 16 hours per week, they’re £649.32 better off than somebody who doesn’t get UC health. For a disabled person who struggles to work, this helps remove a financial disincentive.

Figure 5: Net income for somebody age 25 or over working at the National Living Wage, with or without a UC health award.

Note: The UC award includes the 2025/26 rates of standard allowance and the average Local Housing Allowance amount for a 1 bedroom flat. Graph 1 also includes the UC health element for 2025/26. This means the claimant is entitled to a £411 work allowance. The net income total doesn’t take into account pension contributions or loss of other benefits through work e.g. council tax support.

Cutting the UC health element is unlikely to incentivise disabled people to work. By definition, people who receive UC health have work-limiting conditions which make most, if not all, roles impossible or very difficult for them. While some people receiving the UC health element may feel able to take steps towards employment now or in the future, there’s a lack of available jobs which are accessible to disabled people. There are ways the government could improve work incentives within the benefits system and reduce barriers to work. But taking money away from disabled people isn’t the way to achieve this.

“There's no guarantee that any of these people will be able to find work. And it's not that they don't want to. It's more like it's not accessible to them. The job market right now is absolutely terrible.” - Citizens Advice adviser

Protections in the bill aren’t strong enough

It’s not clear how well people with the most severe conditions will be protected from these cuts.

In the Pathways to Work green paper, the government said that people with the most severe, life-long conditions would see their incomes protected and would be given ‘an additional premium’. The final version of the bill protects people in this group from the cut and freeze to UC health, meaning they'll be on the same rate as pre-existing claimants.

The bill states that those with the most severe conditions will be identified using a pre-existing criteria called the severe conditions criteria. At present, the criteria is used by healthcare professionals who carry out the WCA to help them decide whether it makes sense for somebody to undergo reassessments. People who have a diagnosed condition, who always meet the level of function required for UC health, with no hope for a cure or an improvement in their condition, can be put into the severe conditions group and may not need reassessments.

However, the bill makes some changes to the wording of the criteria, which appear to make it more restrictive. The new wording specifies that disabled people must meet at least one descriptor ‘constantly’, rather than the majority of the time, as is currently the rule for UC health. This would make it more difficult for people with fluctuating conditions to meet the criteria. The bill also states that they’ll need to have an NHS diagnosis. That means that people who struggle to get one, for example due to long waiting lists, may also be excluded.

Whilst the government has given assurances that people with fluctuating conditions and private diagnoses won’t be excluded from the severe conditions group, this is not currently explicit in the wording of the bill. This means less protection for people in these groups.

Stephen Timms has said that the severe conditions criteria is temporary, and a new way of providing protections once the WCA is scrapped will be set out soon [4]. This must address the gaps currently present in the policy, ensuring that people who are unable to work due to their disability are supported.

Who will be impacted?

An estimated 730,000 disabled people will lose out financially due to the UC bill. This includes:

People who become disabled after the cut-off point

People whose condition worsens over time

People who lose UC health and have to reapply

Disabled children who become adults

Each of these groups will be worse off than claimants on the original rate of UC health, despite not having lower costs or less need for support.

People who become disabled after the cut-off point

The cuts to UC health will only apply to people who become eligible for UC health from the 6th of April 2026. Anybody who develops a serious, work-limiting illness after the cut-off point will be worse off than if it had occurred before that date.

This could impact people like Anna:

Anna’s story

Anna* was recently diagnosed with cancer. Because she’s self employed, she’s not likely to earn anything while she undergoes surgery and chemotherapy treatment. Our advisers helped her make a claim for UC and advised her to apply for UC health as soon as possible.

For Anna, receiving UC health will be the difference between being able to afford her essentials and going into debt. The standard allowance of UC alone wouldn’t be enough for her to live on while she goes through her treatment.

However, if Anna had gotten ill just one year later, she’d receive much less support.

* All names have been changed.

People whose condition worsens over time

It’s not only people with new conditions who will be penalised. Those who have progressive illnesses which get worse over time will also lose out, unless they meet the restrictive severe conditions criteria. That’s because the rate of UC health is determined by when you apply and become eligible for the UC health element, not by when you first got ill. This could affect people with conditions like arthritis, Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis. Many of these people will become totally unable to work, but if this happens after the cut-off date, then they’ll only receive the lower level of UC health. This will leave many people with progressive conditions struggling to cope financially.

This could impact somebody with a health condition like Peter:

Peter’s Story

Peter* originally applied for UC health a few years ago but his application was rejected. Since then his health has worsened. His osteoporosis is increasingly leading to breaks and fractures. He struggles to walk and can no longer manage his toilet needs.

Peter repeatedly asked to reapply for UC health. However, it took over a year of requests before his work coach gave him the relevant form to fill out and submit.

While waiting for the extra UC health payments, Peter has built up debt and is struggling to afford his essentials. Despite also receiving PIP, his income is nearly £100 less than his living costs each month. After deductions from his UC award to pay towards his debts, he’s even worse off.

If Peter’s condition had worsened next year, he’d likely miss the cut-off point for protected entitlement to UC health. As a result he’d only be entitled to half the amount of support.

* All names have been changed.

People who lose UC health and have to reapply

The UC bill allows current claimants to remain on the original rate of UC health, but some may lose this protection. For example, if they come off UC for a time or lose their entitlement to UC.

Dan’s story is one example of how somebody may lose UC health:

Dan’s story

Dan* recently had his UC claim closed after he was wrongly imprisoned following a mental health breakdown. Once he was transferred to a psychiatric hospital, our advisers helped him reapply for UC. They also helped him with a new application for UC health.

With their support, Dan was able to get his benefit payments reinstated. But if this had happened a year later, he would have been put onto the lower rate of UC health, despite not really being a new claimant

* All names have been changed.

Additionally, while managed migration from Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) to UC is supposed to be completed before April 2026, some former ESA claimants may miss out on getting the protected rate of UC health. Those who don’t claim UC by their managed migration deadline, and whose ESA claim is then closed, will be treated as new claimants if they later claim UC [5]. This would most likely affect people in the most vulnerable circumstances, such as homeless disabled claimants.

Disabled children who become adults

Protections for current claimants also don’t extend to young disabled people who become adults who qualify for UC in their own right. Young people who are currently getting the child disability element of UC won’t be able to access the original rate of UC health once they move into adulthood. This will affect all young people who become qualifying adults from the cut-off date onwards. There are currently over 542,000 households with a disabled child receiving UC [6].

For somebody who was getting the severely disabled child element of UC, this means a reduction in support from £495.87 to just £217.26 per month. That could affect families like Callum’s:

Callum’s story

Callum* lives with his wife and two sons, both of whom are disabled and receive the highest rates of PIP daily living and mobility. He and his wife are full time carers for them.

His youngest son just turned 19, which means the family will lose the severely disabled child element as well as the child element from September. His son should be eligible for the under 25s rate of the standard allowance and the original rate of UC health because he’s applying before the cut-off date. But if he’d turned 19 just one year later, he’d get about half the amount of UC health.

* All names have been changed.

Conclusion

The UC bill will have far reaching consequences, many of which haven’t been properly debated or understood. What’s clear is that cutting UC health is going to hurt disabled people. Thousands of people will be worse off, at a time when disabled people are already struggling to make ends meet.

The policy rationales given for the changes are ill-thought out and based on misconceptions. Cutting UC health is unlikely to encourage many people into work, and those who are forced into jobs might end up more unwell. While raising the standard allowance is a good idea, the current uplift doesn’t go far enough to make up for the proposed cuts. And while the government says those with the most severe conditions will be protected, many are likely to miss out on support.

If the government is serious about helping disabled people into work, cutting UC health isn’t the way to go.

We want to see the cuts to UC health delayed until a real assessment of the policy and its potential impacts has taken place. We’re also calling for greater clarity and legal protections within the severe conditions criteria to ensure that it won’t exclude people with fluctuating conditions or those who may struggle to get a formal NHS diagnosis.

As the government looks ahead to other proposals in the green paper, as well as the Timms review of the PIP assessment, it’s imperative that they properly consult with disabled people and their advocates. Real, impactful reforms cannot be worked backwards from savings targets.

Notes

[1] Essentials were defined as food, rent / mortgage payments, bills such as energy, water, broadband, mobile and council tax, childcare, transport, insurance (e.g. car insurance), medication and toiletries.

[2] Polling figures quoted are drawn from a nationally representative survey of UK adults conducted for Citizens Advice by Yonder Data Solutions. Total sample size 2,354. Fieldwork took place between 28th February and 2nd March 2025. People on disability benefits - defined as people on PIP, UC - LCWRA element and Income based Employment and Support Allowance - were boosted to 511.

[3] You can see how this is calculated on page 4 of the Universal Credit and Personal Independence Payment Bill Amendment.

[4] Work and Pensions Committee (June 2025). Oral evidence: Get Britain Working: Pathways to Work, HC 837, Q113.

[5] The government has said that those moving from ESA to UC without a gap in awards will be given the protected rate of UC health (see PQ 63563 and PQ 66883). However, under the current legislation, those moving from ESA to UC are considered new claimants, so there’s a risk that those who move after April 2026 will miss out.

[6] Department for Work and Pensions (March 2025). Stat-Xplore: Households on Universal Credit.

This briefing was written by Victoria Anns.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Craig Berry, Simon Collerton, Rachel Ingelby, Edward Pemberton, Maddy Rose, Julia Ruddick-Trentmann, Abi Sheridan, Kate Smith and Becca Stacey for their advice and support with this briefing.